Mark Sfirri

Wharton Esherick: Founder of the American Studio Furniture Movement

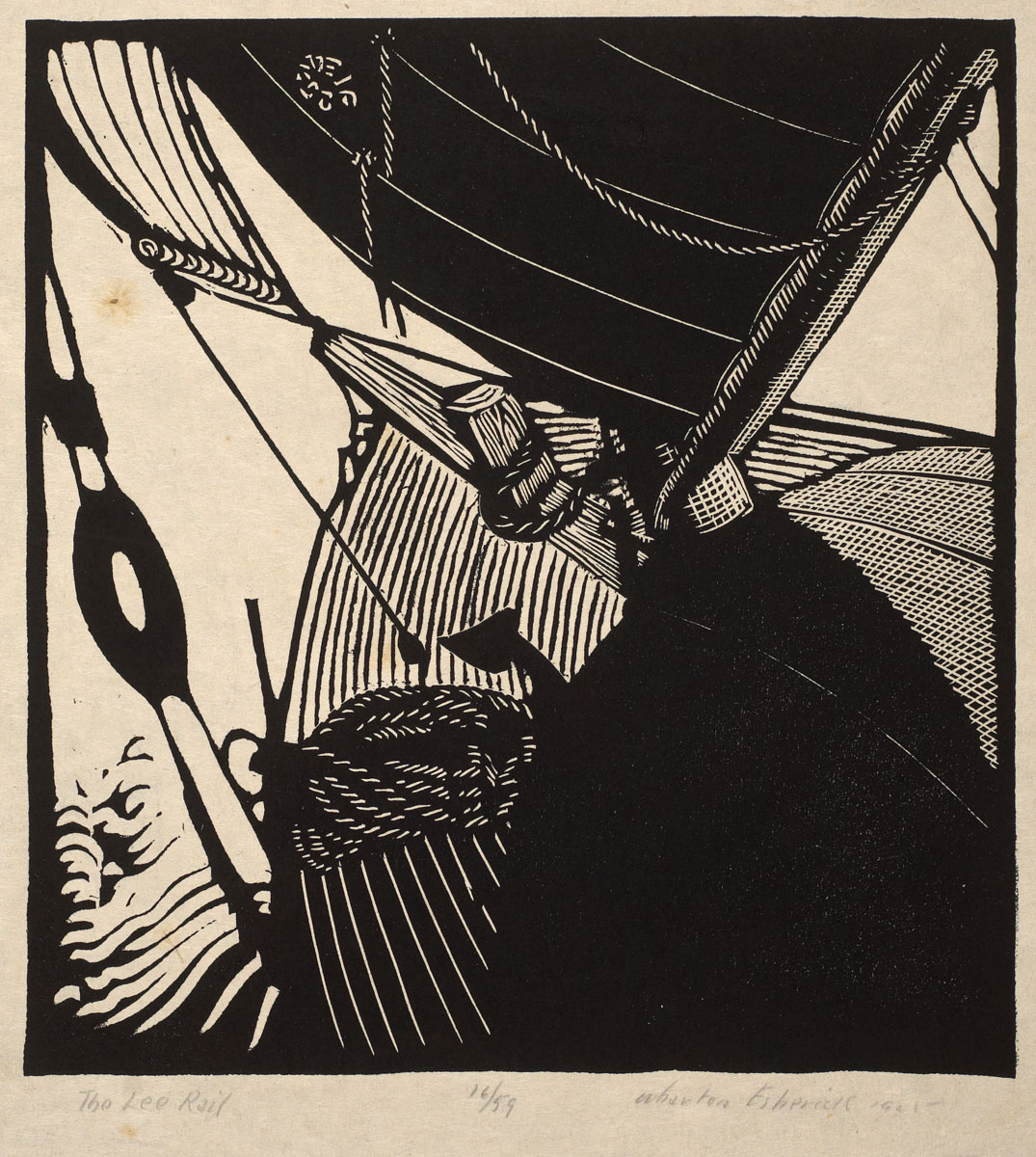

On November 10, in a special program put together by RFC’s artist in residence, Miriam Carpenter— artist, woodworker, and teacher, Mark Sfirri, presented —Wharton Esherick: Founder of the American Studio Furniture Movement, sharing his insights on the life and work of Wharton Esherick. Sfirri’s talk spanned Esherick’s remarkable career— from his early impressionist paintings, through his boldly graphic woodblock prints, through his ceramic, wood and stone sculptures, to Esherick’s works in architecture and, of course, his extraordinary furniture, where he pioneered the art of craft furniture design in the United States in the mid-20th century.

Wharton Esherick was trained as a painter, studying at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Arts and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He started his career in the 1910s, as an illustrator for the Victor Talking Machine Company, of Camden, NJ— creating enchanting images of medieval troubadours, to that of the great tenor, Enrico Caruso. Through the 1920’s Esherick and his wife, Letty, with their young daughter Mary, split their home between Paoli, Pennsylvania, and Fairhope Alabama. Founded in 1894, by E.B. Gaston, Fairhope was based on the principals of the social progressive Henry George as “a single tax colony”— “a model community, free from all forms of private monopoly, and to secure to its members therein equality of opportunity, the full reward of individual efforts.“ Fairhope quickly became a magnet for socialists, artists, and writers.

Marietta Johnson, the founder of the School of Organic Education.

Wharton and Letty were drawn to Fairhope after a lecture by Marietta Johnson, the founder of the School of Organic Education. The Eshericks came to Fairhope to enroll their daughter in Johnson’s freeform progressive school. Eventually, Wharton himself would end up teaching painting at Johnson’s Organic School It would be Johnson who encouraged Wharton to take up woodcarving, which was part of her hands-on educational approach, to help supplement his art income. Sfirri shared an image of a portrait of Marietta Johnson by Esherick with a hand-painted wood frame carved by Esherick’s own hand.

According to Sfirri, Fairhope would prove formative in Esherick’s career. There the Eshericks befriended the socialist author, poet, and pamphleteer, Mary E. Marcy. Wharton’s very first woodblock prints were prepared for Marcy’s children’s book— Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk. Also while at Fairhope the Eshericks’ met the social activist, Florence King, and her husband, Carl Zigrosser-Weyhe, who later would feature Esherick’s woodblock prints at his Weyhe Gallery in New York City. The noted Alabama art potter, Peter McAdam, was also at Fairhope. Working in collaboration with McAdam, Esherick produced a series of whimsical, surreal animal figures in ceramic— some of his earliest works of sculpture. Wharton also met his good friend, writer Sherwood Anderson, at Fairhope. Later, Esherick would introduce Anderson to another friend, Jasper Deeter, of the Hedgerow Theatre— and Anderson and Deeter would work together in turning Andersons’ short story collection, Winesburg, Ohio, into a play for the theater’s pioneering repertory.

Wharton also directly collaborated with Hedgerow— creating posters and graphics, designing sets, and on one occasion, even acting. Esherick first made his now famous chairs, made of salvaged hammer-handles, for Hedgerow’s auditorium seating, in payment for his daughter Ruth’s tuition at the prestigious theater’s school.

Esherick chairs, shown above, made of salvaged hammer-handles, for Hedgerow’s auditorium seating Hedgerow Theatre. "A work of Yankee ingenuity," Mark Sfirri, quoting furniture artist, Wendell Castle.

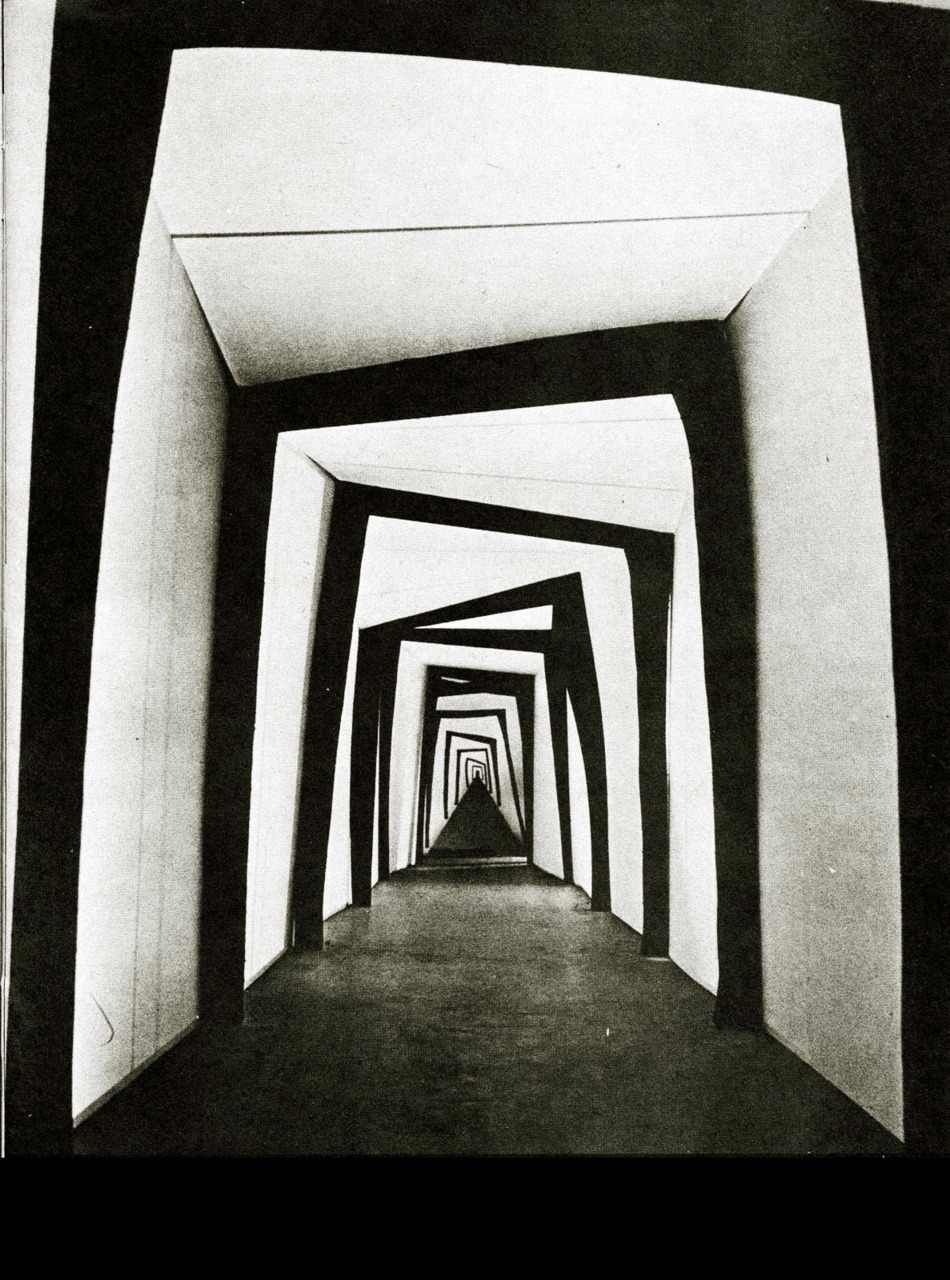

Sfirri compared one print of the interior for the Hedgerow theater to that of a film-set still from German expressionist silent horror film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Sfirri’s next slide cut to Eshericks “Farmhouse Chairs” of 1928, with their similar crystalline forms— each chair similar in design, yet different than each other. Although Esherick never documented it in his writing or interviews, Sfirri, noted that Esherick did have a keen interest in the Swiss Anthroposophical philosopher Rudolph Steiner, the founder Waldorf Schools. Esherick’s library contained many books on anthroposophical studies. Esherick's first encounter with Steiner’s ideas came in 1920 when he was introduced to Louise Bybee. She was a pianist who provided accompaniment for a form of anthroposophist dance— eurythmy. Sfirii then showed a beautifully carved wood table top Esherick collaborated on at the Threefold Farm, a eurythmic dance summer camp in upstate New York, where Bybee played.

Mark Sfirri showed Wharton Eshericks’ Conner Desk circa the ’30s, for his patron Helene Fischer, describing it in depth and proclaiming it, his “favorite piece of Esherick furniture, ever.”

Sfirri then showed a most remarkable corner-desk that Esherick designed for his patron, Helene Fischer of Philadelphia. For Sfirri, it is one of Eshericks’ masterworks. This is the first piece that seized Sfirris’ attention at the exhibit— Wooden Works: Furniture Objects by Five Contemporary Craftsmen, that included George Nakashima, Sam Maloof, Wharton Esherick, Arthur Espenet Carpenter, and Wendel Castle, at the Smithsonian Renwick Gallery in 1972. Sfirri credits this desk’s amazing design to the engineering ability of Esherick’s assistant cabinetmaker, John Schmidt— a master-craftsman trained in Germany. To Sfirri, Esherick is primarily an artist and designer and had only modest skills as a woodworker. It was with the craft and joinery skills of Schmidt that enabled Esherick’s designs to be composed of prismatic elements, weird angles, and biomorphic forms.

Sfirri closed his lecture noting that although today Esherick is recognized as the leader of the Studio Furniture Movement, Esherick thought of himself primarily as an artist, not a craftsman. According to Sfirri, Esherick was concerned with form, not technique. He pursued his artistic vision in forms. Every work, whether in painting, wood picture frames, woodblock prints, wood or stone or ceramic sculpture, architectural elements, set design, or furniture— all were opportunities in exploring form, of making art.

Mark Sfirri—Artist, sculptor, woodworker and teacher, Mark Sfirri, has been studying and researching the life and work of Wharton Esherick (1887-1970) for over a decade. Mark Sfirri has authored eighteen articles on history, design, and technique for a variety of craft publications and authored six articles on Esherick for Woodwork and Journal of Modern Craft.